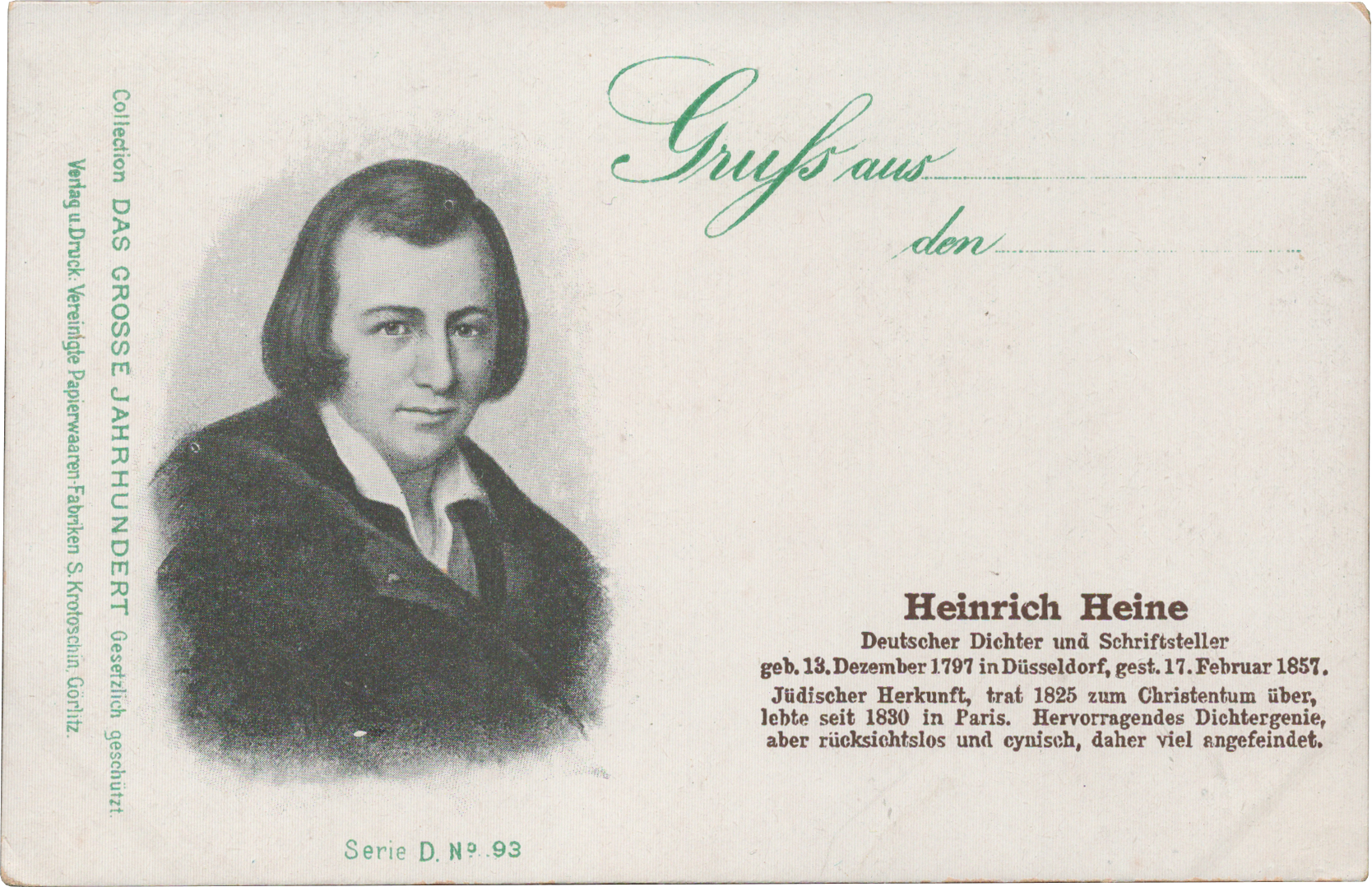

Heinrich Heine

Greetings From [space for the place]. The [space for the date]. Heinrich Heine. German Poet and Author, born 13 December 1797 in Düsseldorf, died 17 February 1857. Of Jewish Extraction, Converted to Christianity in 1825, Lived in Paris from 1830. Outstanding Literary Genius but Ruthless and Cynical, Hence the Target of a Great Deal of Hostility. Collection: The Great Century. Vereinigte Papierwaaren-Fabriken S. Krotoschin, Görlitz. Before 1907.

Now widely considered the greatest German-language poet of the nineteenth century, Heine was also a satirist of extraordinary acuity, and it is indeed little wonder that many Germans responded with extraordinary hostility to his lampooning of their provincialism, bigotry and pettiness. Few had any difficulties explaining his lack of appreciation for them: he was, after all, regardless of his conversion, a Jew. In the nineteenth and early twentieth century, all things Heine were embroiled in a vicious culture war, and few things triggered German patriots in quite the way proposed or actual Heine memorials did. Nobody, one Jewish periodical wrote in 1897, demonstrated the “affinity between the specifically German and Israelite spirit better than … Heinrich Heine, whose name, alas, one cannot mention today without having to fear one might be stoned by a certain party that claims to have monopolized what it means to be German”.

Simon Krotoschin (1860–1930) later moved his paper and stationery business from Görlitz to Zeitz near Leipzig. At some point before the First World War, he merged with Wezel & Naumann, becoming its managing director. In 1942, his widow, Gertrud Krotoschin, née Friedländer (1879–1942), was deported first to Theresienstadt and then to Treblinka where she was murdered.